The other day I was challenged by one of my students for making a speciesist comment.

We were talking about grey squirrels.

He was in the middle of writing on essay on “Methods to humanely kill” said species of squirrel {for context, I supervise students on various animal welfare and ethics Master’s degrees) and was really struggling with it, as such a view was in stark contrast to his own fundamental beliefs.

In an attempt to reframe it and help him complete the essay I, rather glibly, said something like, “Well they are an invasive species who are out-competing the native red squirrels and putting them under threat so, I mean, humanely killing them is probably fairly necessary”. I went on to describe my daily dog walk where, more than any other mammal or bird, the grey squirrel is by far the most frequent and common animal I see each day. On one walk, I think I counted 30 different grey squirrels scampering boldly about the park I walk through.

“That, to me, doesn’t seem like an ecosystem in balance,” I said, “I mean if you were to put the red and the grey squirrel side by side, which is more important? I’d say the red, considering how adapted it is to this environment, it’s a native part of it, evolved to the habitat of this country, the grey squirrel is just taking it over”.

“That’s speciesism” he said, rightly challenging my favouring of one species of squirrel above the other.

“Yes. Yes, it is” I said, leaving it there.

I’m currently participating in a course on “Decolonizing relationality in Ireland: unravelling whiteness and Irish identity” run by Jimmy Ó Briain Billings of Tuiscint na Talún. Beyond the more cognitive exploration of colonialism, modernity and whiteness, the course also encourages a daily land practice. Each week, we are given a different land-based question to explore as part of this daily practice.

It just so happened that the same week as this grey squirrel conversation the course tasked us participants to “Observe some animal relative on the land you’re on” and ask ourselves “How do you think colonialism and modernity have impacted their lives?” and “What kinds of experiences might they be having (or not having) that are linked to colonialism?”.

The squirrel, then, has been my guide and teacher this week, scampering their way through my mind in a complex series of philosophical knots that have forced me to rootle through the assumptions and entrenched paradigms that exist there.

I thought about how the grey squirrel is only here (in the UK and Ireland) because of colonialism. Taken, as they were, from North America and brought to England in 1876 as an “ornamental species to populate the grounds of stately homes”. The same happened in Ireland in 1911 when six pairs were released on the grounds of Castle Forbes in Co. Longford.

I thought about the parallels between the maps I’d seen depicting European colonial expansion in North America and the spreading grey squirrel populations across Ireland and the UK. Both illustrate an encroachment, a taking over of territory and habitat by an alien, an evisceration of the home of the indigenous humans and non-humans.

I contemplated how the ‘colonial’ grey squirrel is affecting the lives of the native red squirrel, out-competing them for food, taking their territory and infecting them with the squirrelpox virus they are immune to. Replace ‘grey squirrel’ with ‘European’ and this could easily be an account of colonisation in North America, and elsewhere in the world.

And so, my thoughts of course turned to Ireland. To how the narrative of ‘invasive’ grey squirrels pushing out, eviscerating and taking over the lands of the ‘native’ red squirrel has such close parallels with the colonisation story of Ireland. The invading English taking over the lands of Gaelic people, brutally eviscerating their culture and pushing them to the margins.

The generational effects of those traumas are something many are now starting to look at and to take seriously. Many wonderful people are doing the heavy lifting; healing wounds that stretch across a vast epoch of Irish ancestry; addressing its impact on Irish cultural traditions and language, and highlighting how it has impacted our relationship with the land and how we use it.

Most of us in Ireland would probably identify more with the red squirrel than the grey (within the very simple parable I’m presenting here). The dominant story of Ireland’s colonial history encourages us to.

As an Irish person living in England, the ‘red squirrel’ story is certainly the skin I default to — an outer armour poised to bristle with quivering affront at another potato joke and always ready with a few facts about ‘those 700 years’ (of colonial rule). As someone I went for a walk with recently said “You’ll never let us Brits live that one down will you”.

And yet, the colonial story of Ireland is, of course, not as straightforward as ‘grey vs. red squirrels’ (although I do not know the inner world of a squirrel so can’t really comment on the straightforwardness of theirs either!)

If we were to broaden the colonial story of Ireland out beyond its edges, then things get much more complicated. Many Irish people throughout history have adopted and ‘taken on the skin’ of the grey squirrel in places like Canada, the United States and Australia. A survival mechanism, you could say, but it’s an aspect of the colonial story of Ireland that many of us don’t want to look at or don’t really know much about. It’s oddly more comfortable to be the victims of colonisation, to only recognise the red squirrel story and disassociate from our grey squirrel cousins. We can defend ourselves from any highlighting of the latter with rejoinders like “Sure the Irish were the first slaves” and “Ireland was England’s colonial proving ground”.

A more faithful (and more challenging) account of the former is that the Irish who were forcibly sent to the British colonies in the Americas and the Caribbean were sent as indentured servants; a brutal and horrific existence but one that is qualitatively different to the chattel slavery of the transatlantic slave trade imposed on Africans (I really enjoyed this really excellent talk for helping me understand the differences).

And while Ireland as the ‘proving ground’ for British colonialism is fairly reflective of the 19th century (e.g. Britain used Ireland to test out new systems of modernity, such as primary school education, before introducing them to Britain), the idea that what the English learned in Ireland was applied to the colonisation of North America has been revealed to be much more complex by the detailed work of Audrey J. Horning. Rather than Ireland as the ‘proving ground’, her work describes the colonisation of Ireland and North America as occurring in parallel; what was done in one place was entangled with the other in a disorganised mess of ‘we don’t really know what we’re doing so we’re making it up as we go along’ English colonial expansion. (Horning explains her research really well in this podcast episode. And if you want an alternative perspective that disagrees with her’s, this article by Nicholas Canny sets out the main critiques).

The nuance and complexity of it all are overwhelming, and so I wish I could stay with the nice strightforward red vs. grey squirrel version of the past.

And yet, I can’t, because while it is so much easier to stay with my red squirrel skin getting pissed off about potato jokes while living in England, I have to hold my hands (paws) up and address that I —in terms of my ancestral heritage— am more grey squirrel than red.

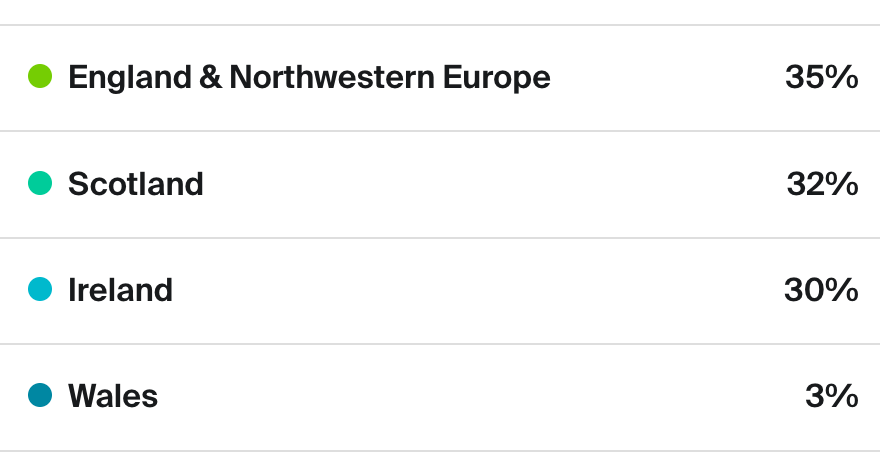

A few weeks ago, I did one of those Ancestral DNA tests:

That my DNA is roughly in thirds of the nations of the British Isles came as no real surprise. It reflected the little bit I know about my ancestry. My paternal side (the Vigors bit of me) has pretty strong grey squirrel heritage. A Norman surname (and later French Huguenot) the first Vigors to arrive in Ireland — Rev. Louis Vigors— came from Devon, England and is listed as the Vicar of Kiltaughnabeg and Kilcoe, Cork between 1615 and 1635. Although I don’t know the details, I think it would not be such a leap to suggest he was a Protestant Vicar serving Protestant settlers who had arrived in that area as part of the Munster Plantations in the 1580s — invasive grey squirrels who’d taken the land and territory of the native red squirrel.

As for his descendants, apart from having a penchant for some very odd names (like Urban, Aylward, Stafford, Forbes and Bartholomew), the running theme is of churchmen (lots of Revs.), politicians, soldiers and farmers (and one zoologist). By all accounts, it’s a fairly imperial-looking family C.V.

Very grey squirrel then.

And yet, somewhere along those last 400 years some of those grey squirrels obviously met and (some, at least) fell in love with some red squirrels and saw themselves as red squirrels too.

As much as I would like it to be (especially when responding to potato-based jokes) there is no simple red vs. grey squirrel story there.

My ancestry reflects the story of a land that has been populated by waves of migration and invasion. Like many in Ireland, if you go back far enough (and account for the diaspora), I am a product of both the colonised and the coloniser. An epigenetic minefield of intergenerational colonial trauma and accountability.

How to unravel it? How to decolonise as both the colonised and coloniser?

I returned to the argument I had put to my student. How I justified, within the context of conservation, the eradication of vast numbers of wildlife to protect one —the native— species over another —the invader. And there I saw it. How such a view relies utterly on a key construct often housed within colonialism — anthropocentrism. For it is only within a paradigm that situates humans above, and separate to, non-human animals (and other humans), and nature that an argument such as the eradication of an entire animal species, invasive or not, could even be suggested. Outside of an anthropocentric lens such an argument becomes morally untenable.

Such a realisation introduced and confronted me with the reality of the colonolialism that exists within my mind. There, out of the corner of my eye, I got a momentary glance of how one of its central logics was opearing behind the scenes, influencing my thinking without my conscious awareness.

“Euro-Western thought and colonial imperialism shaped species perception

through methods of collecting, preserving and curating that cultivate speciesist hierarchies”

Seeing this has made me realise that addressing how red or grey squirrel I am, or what damaging imperial systems some of my ancestors were complicit in shouldn’t be what I’m worrying about or trying to unravel (at least not for now).

The better place to start is uncovering the colonisation within my own mind. To decolonise at the individual level.

I have little idea or knowledge of how to do that. But through the Decolonisation course, I am learning.

“Start with relationality” has been the main message — to see the interconnectedness in all things, the interdependencies that exist between humans, non-humans, the natural world and the spiritual realm. To see nothing as separate to but as a part of.

Such a perspective has a certain beguiling, ethereal loveliness about it. And written there, as it is, seems straightforward. But the reality, as my lesson from squirrels this week has shown me, is much more challenging. Because both my mind and I have been socialised and bathed in a world were colonial ideologies and narratives are the dominant and the default. So dominant and default that we’d hardly think of them as ‘colonial’, they are just the way things are.

And so, I must take a step back and socialise myself in a different way — get socialised by the interconnectedness and interdependencies of the natural world.

Maybe I’ll start by getting to know my squirrel neighbours.

Thank you for this. There is a nascent body of literature here in the States that if one looks beyond all the screaming nonsense in the mainstream, can be found and contemplated about how the colonized become the colonizers, regardless of race, nationality, and religion.

Thanks Whitney, would you have any recommendations? Author and text wise for me?