Different sides of the hearth: gender differentiation in Ireland

A brief note on how gender is a social construct with weight and meaning in Ireland, and how that shapes us

“Although all societies are characterised by sexual asymmetry to some extent, one would be hard put to find a society in which the sexes are as divided into opposing alien camps as they are in any small Irish village of the west. A general rule can be said to be observed: wherever men are, women will not be found, and vice versa”

Nancy Scheper-Hughes: Saints, Scholars and Schizophrenics (pg. 186)

Any visiting alien from another planet would, on arrival, quickly come to the conclusion that, in Ireland, gender matters.

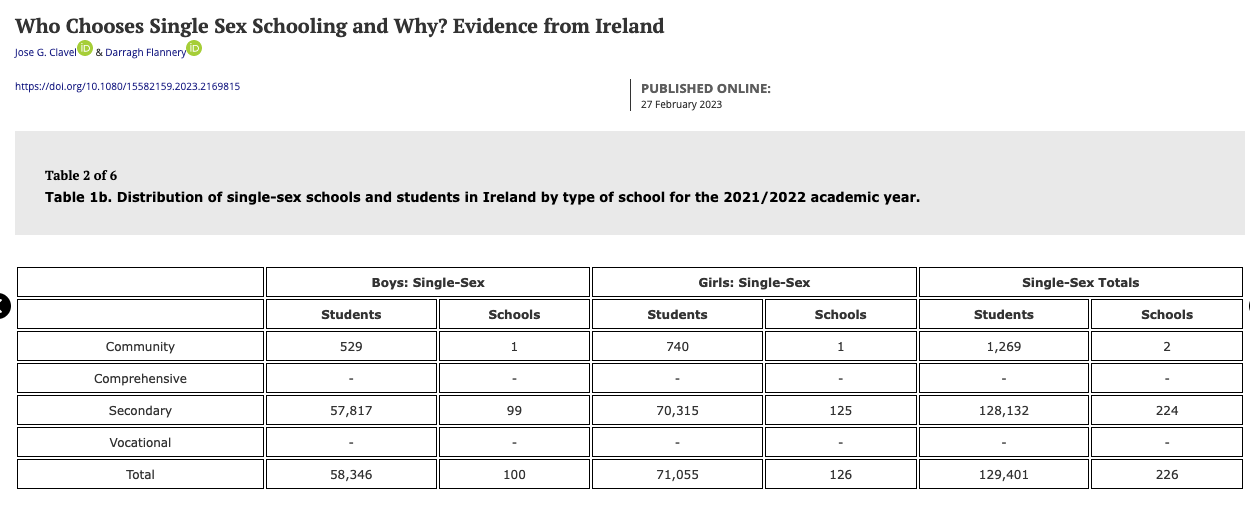

Compared to the rest of Europe, where co-education is the norm and single-sex schools the exception, Ireland has an unusually high proportion of single-sex schools (roughly one-third of schools), with girls making up the greatest number of students in single-sex education in Ireland:

Traditional gender norms which emphasise role differentiation and what behaviours are expected for different genders are also an important part of the everyday social world in Ireland.

The governments’ Gender Norms in Ireland Report (2021) found that that “a significant proportion of the population believes that the most important role of a man is to earn money and the most important role of a woman is to take care of her home and family”. A notable proportion of the population also holds norms that “men should work in ‘manly jobs’ and should be ‘manly leaders’” and that despite the vast majority of people supporting that men should do an equal share of housework “the norm of men not doing unpaid care and domestic work remains visible in data from Ireland”.

The EIGE’s (European Institute for Gender Equality) finds that women (compared with men) spend much more time engaged in domestic and caring responsibilities:

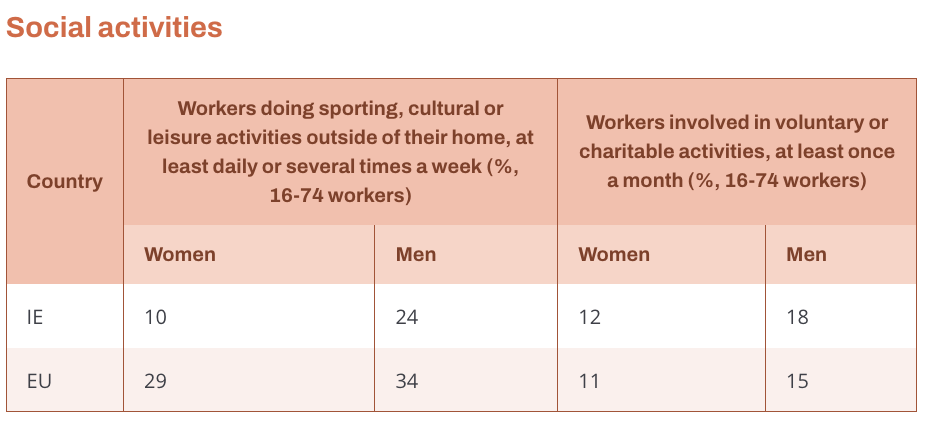

This eats into the time they have available for leisure activities and a life beyond caring for others, domestic duties, and work. The same EIGE report found that only 10% (read that again. Only 10%!!!) of women in employment in Ireland engage in (i.e. have time for) any social activities, compared with 28% of men:

Gender is a social construct and, in Ireland, it’s very clear that it is one which carries significant weight. It shapes, not just how people are viewed and referred to, or how they see themselves, but their very life-course — it’s as if how they spend their time, and how they think, act and behave has been pre-determined by the roles, behaviours and expectations Ireland associates with their gender.

I liken it to a ‘Script’ — a gender-based play-book, which Act by Act, and Scene by Scene tells you what is expected of you as e.g. a girl / a woman of Ireland.

My wild imagination thinks of some dystopian novel I could write based on it, where the government hands out little books to children at birth (probably in shades of pastel blue or salmon pink), the official harp emblem across the top with the title “An Treoir do Chailíní — The Guide for Girls” or “An Treoir do Bhuachaillí — The Guide for Boys” on the cover. An official instruction manual, with a foreword from Gay Byrne (again in my dystopian novel), for ‘good little girls’ and ‘good little boys’.

The most prevalent message or the central ‘Act’ in the ‘Script’ is that women are responsible for the domestic sphere and their primary function is to care for others. I see, from the childhood reflections of many of the women interviewed, that this is something taught to girls of Ireland from a young age and is often the specific point where they realise “gender matters” — that they are treated differently to boys, subject to a whole set of different expectations to e.g. their brothers.

Orla, a child of the 1990s, recalls how the expectation for the women in her family was

“Always look after your neighbours and look after anyone who needs the help and look after the men as well…. And I remember Mam [asking my older sister]…. to tidy up my brother’s room or something when she was about 15, and [my sister] was like ‘Absolutely not! This is not happening’. Whereas Mam thought that was perfectly okay. She always cleaned up after the men, that sort of thing”.

While Grainne remembers not only the level of expectation placed on her to look after the domestic world, but also how clearly her brother did not receive that message:

“I was still heavily relied upon in the house. My mum had gone back to work then as well. And my sister was six years younger…. she was only 10, 11. So I was helping out at home. And yes, I do always remember having the extra responsibilities…. My brother is two and a half years younger than me. And I also remember his roles being different to mine. And if he didn't do them, I ended up doing them. So I always had that sense of, you know, the feminism in myself saying it's not fair. And I always remember voicing it as well…. And I said no. I wasn't putting up with that. I wasn't putting up with that. It lasted for a while, but not for very long. I felt Mammy was very soft on [my brother]”

Is it any wonder then, when this is the ‘Script’, the guidebook that young girls are given that they grow up into women who not only shoulder but deeply feel that caring for others and domestic duties are their responsibility and are left feeling guilty if they take time for themselves.

Statistics rarely show what goes on behind the scenes, what is really behind the numbers — and I wonder how much of that shocking stat that 90% of employed women in Ireland don’t engage in social activities is influenced by them feeling that they can’t and shouldn’t take time to do things for themselves because the ‘script’ has raised them otherwise?

When I read it I thought of how guilty Deirdre, a woman of Ireland Project participant felt, when she decided to do something she had always dreamed of — join a choir:

“[I joined a choir and] fell madly in love with it. Re-found my voice. I had sang in choirs as a child — was never an amazing singer — but loved to sing. Loved to sing…. So, got this lease, [a] new lease of life in a way. Something just for me. And I remember feeling; finding it very hard to give it to myself. That guilt that came through our generations of women is so strong. Whether it be towards your children or your parents, to give yourself something, do you know? It's powerful, played a huge part of my life; the constant shame and guilt of not being able to give enough to others and to give something to myself, [that being] so difficult, to [just] give [myself] something just for me”.

This is how the ‘Script’, or just one singular aspect of it (being responsible for the care and needs of other before your own), cascades down through women’s lives. When it becomes not just an externally handed out ‘guide’, but has assimilated into the woman’s own inner guidebook.

As Fiona highlighted in her interview, that aspect of the ‘Script’ for women, and how differentiated it is from the ‘Script’ for men, has been so successful that is recognised as:

“The Irish woman’s way, isn’t it? To take [care of everyone else and the home]…. and I do it! I do it with [my partner]. But I don’t like to say that I do it, if that makes sense, because it’s nearly — it’s not embarrassing but it’s like if we [as women] want to be progressive, we can’t be just seen as the primary caregiver in the home…. It just can't be the way if we are also working full time and building careers for ourselves, there has to be an element of teamwork there. But I think maybe Irish men, or the Mammies have ingrained it into them that they're precious. And that's lovely for them, that they know that [but] I don't think Irish female children got the same 'precious child' kind of thing. It's like, okay, well…. we're going to train you up now, we'll start you off with sweeping the floor there at three years old”.

In Ireland then, gender matters, it truly does. Stats and gender equality markers continue to highlight Ireland as a success story — a country that has made exceptional improvements (with the odd backslide here and there) in gender equality at rapid pace. But numbers and percentages belie a whole universe of cultural complexity — of social scripts and norms and traditions and attitudes and behaviours — that is much harder to capture and much slower to change.

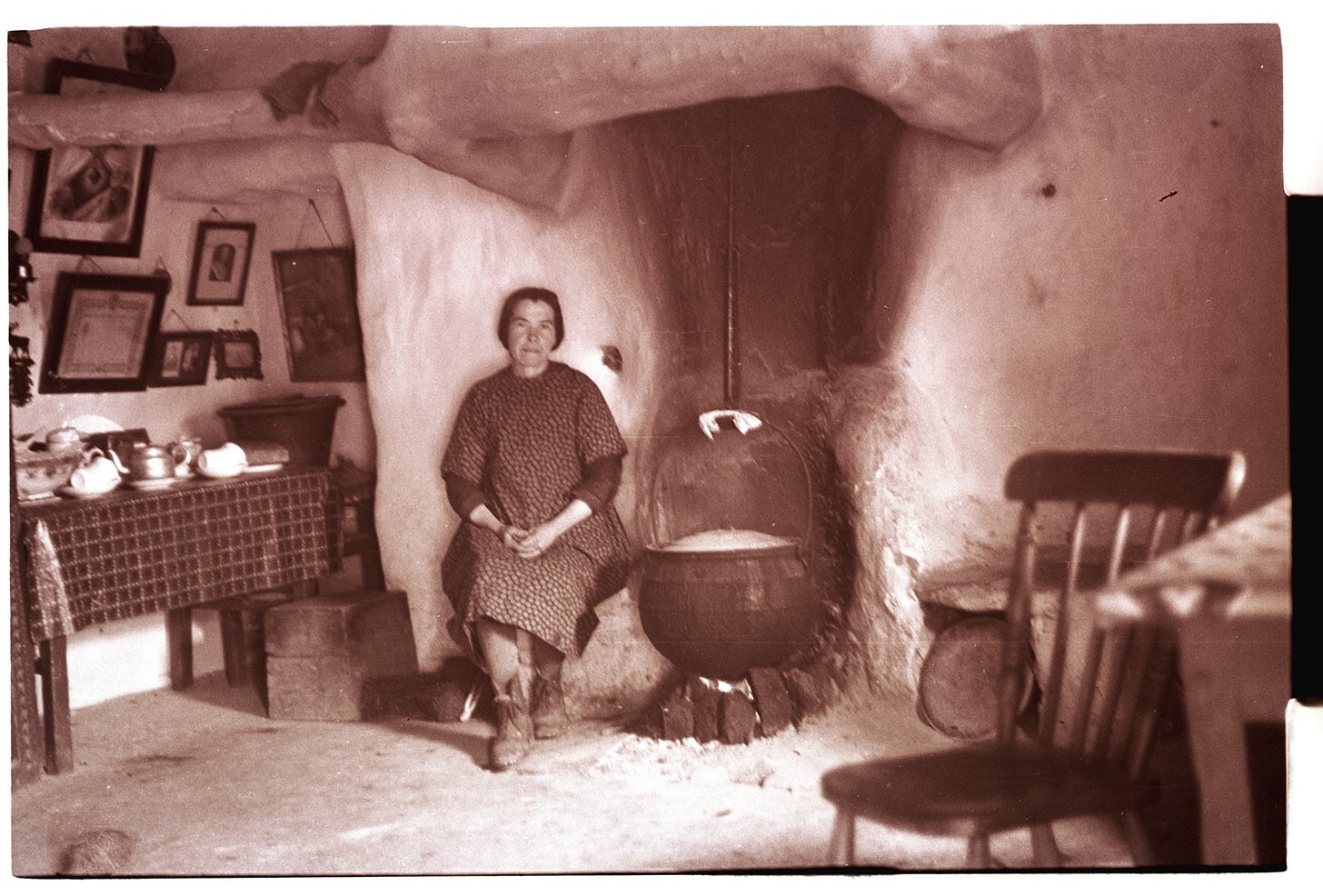

Archaeologist and geographer E.Estyn Evans’ once made the observation that in the traditional Irish kitchen of the early 20th century, there was a clear gender segregation delineated by the hearth: men sat and stored their possessions to the right, and women the left:

“There is an old belief that the left-hand keeping hole [of the hearth] belongs to the woman and the right-hand one to the man of the house. Here you may see in safe-keeping, on one side the woman’s knitting, on the other the man’s clay pipe”

And from what I’ve seen in the stories of the women I’ve interviewed; Irish society is still very much sat at (and set up around) that hearth. There’s goodness in that (some merit) and also great challenge, but it’s hard to meet those challenges when the different parties have, for so long, been raised to learn the part they play from two very different ‘Scripts’.

V interesting Belinda. As I read I wondered about the age group of the women you quote? It would be too depressing to think this attitude is as fixed in younger adults.

Those are good qualities though. We should teach them to everyone! maybe men have similar loads put on their shoulders?

Personally, I no longer chafe against gender roles as long as - the workload falls evenly, and no one is HAS to do a,b,c.

The world is very big and earning a living /running a home / raising a family is difficult and intense. There's enough work and more for two adults to both fail at achieving it.

Historically, say in farming communities and other physically demanding environments, it would make perfect sense the work to be split between physical demanding and childbearing. In ireland we're still quite rural and attitudes don't change that quick - another generation or two of email jobs and contraception should do it

And one other point - women who feel guilty about taking an hour or two a week for themselves need to work on themselves, I say this with compassion. It's the same with any flaw, drinking too much, flying into a temper all the time, being a workaholic . No matter the externalities, a woman has to look at her life and assess what's objectively true and power on through to a better place. It's better than expecting universal approval for your actions.