Apples and community

Thoughts on community in the absence of a 'common form of life' and when all the women are worn out keeping it going

I am exhausted with apples.

We live in a very old house with a very old, wild and overgrown orchard. A solitary pear tree. Two damsons. Two plums. And apple trees apple trees apple trees apple trees. Eating apples that are crisp and sweet, and fluffy and dry. Big tart green ‘Granny Smiths’. Auburn coloured cooking apples that have the look of ‘heritage breed’ about them and several other varieties in between.

More than I know what to do with.

More than I have the capacity / ability / interest to do with.

But I feel guilty about leaving them to fall and rot on the ground. An ungrateful waste to the abundance nature has worked hard on all year.

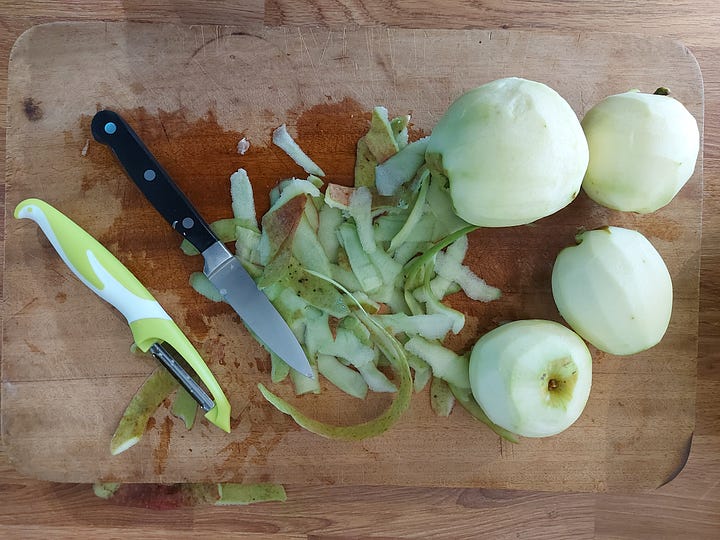

So, every other day I go out and collect the windfalls. Every spare bowl and bit of crockery in the kitchen put to use to containing them and then, I set to. I peel and core and stew. I look up recipes for Jams and Chutneys. And fill my largest saucepans with bubbling, vinegary, sugary, concoctions. Try my hand at making apple cider vinegar. Google ‘what to do with apples recipes’. Wonder whether a cider press might be a genuinely good investment. Wash the eating apples. Wrap them individually in old newspaper and hope they’ll keep for the months when apples might be an enjoyable novelty again.

And as I stand for hours in the kitchen peeling, stirring, washing, scrubbing, jarring, burning, worrying (will it set?), wrapping, labelling, I think about how, in times past, this old, raftered, farmhouse kitchen would have been a flurry of activity — women, several women I imagine, working together to make good the harvest, telling jokes or stories to pass the time and making up games with the apple peels (like the initials they spell when dropped on the floor — those of a future love).

But I am alone and worn out with all the apples, my hands and arms fatigued by doing work once shared.

Community, reciprocity, neighbourliness and those things apparently so inimical to them — modernity, capitalism and neoliberalism primarily — have been on my mind lately. Well, more so on the periphery. But, I trust the things that repeatedly show up on the sidelines of my thought usually do so because they want attention.

Except, I am not really sure how to attend to such complex, convoluted thoughts as to all the ways that so many things I am watching, reading, hearing, listening, discussing, debating all seem to conclude that our modern life is antithetical to ‘proper’ community.

Where to start with such a topic.

A definition of community, perhaps.

I quite like this one:

A community is any set of individuals who (1) share with one another, in whole or part, a common life or form of life; (2) attach — and are aware of themselves and each other as attaching — intrinsic value to that common life or form of life; (3) feel, or are disposed to feel, some degree of heightened regard for one another; and (4) cooperate, or are disposed to cooperate, with one another to preserve and foster that common life or form of life1.

Straight away, I am struck by how so many of us craving community and/or lamenting the loss of the ‘proper’ communities of the past would struggle to address the first point. Very few of us ‘these days’ have a common life. Our lives are vastly different from our neighbour, our old school friend, even our work colleagues and we are all, individually, very busy with them.

I think often of something the oldest women I spoke to about being ‘a woman of Ireland’ (a woman in her 90s) told me. How she responded to my queries about how life for women had changed from the time of her own mother to that of women today; the life her daughters and grand-daughters lead.

She couldn’t and wouldn’t compare the life of her mother to the life of women today she explained. There is no comparison. Her mother was a full-time housewife on a large and busy farm in the days when such a role was physically and intensely demanding. Her days revolved around the farming calendar, feeding and taking care of the workmen who lived and worked on the farm in addition to her own family. She was a woman who had a ‘wash-day’, a ‘bake-day’, and a particular day of the week to clean the stair rods (I can’t even imagine). Her days had a consistency and a rhythm. There is no comparison.

Even thinking of her own generation of women, she noted how similar their lives were.

‘We were all going home to do the same things’, she said. At any time of the day she could look out the window across her neighbourhood and she knew exactly what all the other women were at, at any time of the day — because it was what she was at. Their lives were not identical, but they were similar, familiar.

They all shared in a common form of life. And commonality is the base-level of community.

Today, few (if any) of us share a common life with our nearby neighbours. Except that we’re all busy with the same hustle — the work, the grind, the deadlines, the bills, the rent, the mortgage, the car finance, the gym membership; the constant servicing and upkeep of our comfortable, modern lives.

If anything, then, the widely pronounced belief that capitalism (and neoliberalism) has (negatively) impacted community begins with how — in the opportunities it has opened up for a more individually-determined and directed-life (and the agency and autonomy that brings)— it has eroded the gel of commonality and similarity between people.

Sometimes it seems like the only thing we share in is that we are all busy all of the time (but with our own individual lives). The women of ‘we were all going home to do the same things’ generation were busy too, but they were busy ‘doing the same things’ and that meant they could do them together, or help and advise one another when they faced similar problems.

At this time of year, I imagine they’d be flat-out jam making too (and canning and preserving). Maybe they’d drop over with a glut of raspberries from their garden, and I’d gladly hand over bags of cooking apples in return. But I’m stood in a steamy kitchen, alone, stirring a pot of jam that doesn’t want to set (apples are very tricky, my jam-expert mother warned) knowing that not a soul on my road is doing the same. And I don’t even really like jam.

There’s a tendency to idealise the past. To highlight the glory of the ‘good ol’ days’ when ‘neighbours were neighbours’ sharing resources and helping one another out. But I am under no illusion that they were anything but truly tough (and the lives we have now are objectively better; I for one like my modern, comfortable life). I’ve read enough first-hand accounts of women who lived through the years when capitalism and ‘modern conveniences’ arrived in Ireland to know that people welcomed it all with open arms because the times of ‘collective jam-making’ and a shared common life rested on a reality of drudgery and hardship.

Siobhán: “If you ask people would they live their lives again, a lot of people say yes, but my mother wouldn’t. She was working morning, noon and night. We lived in a two-bedroomed farmhouse. There were eleven children in two bedrooms. As children we had oil lamps. Oil was rationed during the war and if your ration went before your next was due that was just too bad. We had no modern conveniences at all, not even cold running water. It all had to be drawn. Times were desperately hard. I remember my brothers going to school without shoes. It doesn’t bear thinking of about from those times to now. Everyone was in the same predicament, that is the reason we survived it, you see”.

Molly: “I look at all they have now, and I look back and think of all my mother had to do. She was on the go all the time as far as I remember. Only for that my father was good, we’d never have managed”.

Two women interviewed in the 1980s by Jenny Beale for her book “Women in Ireland: Voices of Change”

Then there is the aspect of community functioning that, in our nostalgic dreaming and yearning, often gets overlooked but which I spend a lot of time writing and thinking about here, as part of the Women of Ireland Project:

The disciplinary actions required to maintain social cohesion and reinforce the ‘common form of life’.

Without common social norms it would be difficult to maintain a ‘common form of life’ and this is where things like shaming (and its close cousins passing-remarks, negative judgement and belittling) become essential, because shaming “broadcasts particularly strong signals about social norms”2 and disciplines those who deviate from the ‘common form of life’ to come back in line.

And shaming, as we all know, is something Irish culture does excellently (and I say this with both sincerity and sarcasm) and, as history and the personal experiences of most people of Ireland can attest, such punitive forms of communication are most often employed in service of maintaining or achieving community equilibrium at the expense of the individual.

In short, the psychological harm of the individual is of lesser importance to servicing, reinforcing and maintaining the ‘common form of life’.

So many of the women I have interviewed for the Women of Ireland Project describe a desire for a greater level of individualism. To unlearn and break free from the conditioning of the collective — the shame, the guilt, the strong sense of duty they feel towards those in their family and community, and the constant prioritising of the needs of others before their own — and be their ‘authentic selves’. And, indeed, both in reflection of this and my own inclinations as a highly individual, independent and self-determined person, much of my theorising, thinking and writing in relation to the Women of Ireland Project has been dedicated to ripping apart all the trappings of Irish culture, the majority of which are the product of collectivism (where group loyalty and community welfare take precedence over the welfare of the individual).

But, I’ve never felt entirely comfortable doing so and recently, the gnawing, nagging sensation which accompanies my evisceration of ‘things that maintain the common form of life in Ireland at the expense of the individual’ has become louder. Because, fundamentally, I do not believe that chasing our individualism will fix what has wounded and burdened us in the first place — a broken ‘common form of life’, a broken community system.

I’m slowly working my way through Jenny Beale’s ‘Women in Ireland: Voices of Change’, a book written in the early 1980s which did pretty much the same thing as the Women of Ireland Project — interviewed women of Ireland about their lives. The accounts of the women fascinate me for many reasons, not least for how similar their experiences remain to the women I’ve interviewed forty odd years later, but especially for how they lived through and bore witness to a significant period of social change in Ireland — namely, the gradual decline of a largely subsidence-based agricultural economy and its associated high-levels of collectivism to capitalism, the adoption of neo-liberal economic policies and the accompanying effects of this on the social fabric of everyday life.

The women interviewed describe how the goal of everyday life “shifted away from neighbourhood cooperation towards individual achievement”3 and eradicated the ‘common form of life’. However, the gender norms and roles which had traditionally accompanied this ‘common form of life’ — of women as the primary care-takers performing the emotional and physical ‘labours’ necessary to uphold, maintain and reproduce community and family — did not change. Rather, women found themselves increasingly isolated from a wider network of community support yet still expected to uphold such ‘labours’ which, for previous generations, had been a shared responsibility (albeit, across a local network of women).

Maura compares her mother’s life to her own: “There was a great closeness, there was no television on the road and they had a great support system, helping each other with their babies. We’ve been living where we do for two years and we hardly know the people round us. It isn’t like the place where I grew up where we were running into people’s houses all the time and the doors were always open. We are much more closed off”.

Maura, a woman interviewed in the 1980s by Jenny Beale, pg. 45 in “Women in Ireland: Voices of Change”

Ireland is a relationship-based (as the functioning and form of the Irish language attests) culture operating within an individualistic, neo-liberal capitalist social system and — because cultural change is slower than social change — we continue to be governed by the values and behaviours of the former while performing the goals and ideals of the latter.

It is here, in this mismatch between cultural and social norms, that I see the root of why so many of the women I have interviewed are crying out for a bit of (in their own words) ‘selfishness’, ‘authenticity’ and self-prioritising over self-sacrificing. Because while the social system has changed the cultural expectation that women are responsible for community and family life has not. What once was a shared responsibility (between women of a family or locality) is now done in isolation (they are the ‘capable women’ holding together an entire family ecosystem) and, consequently, they are burdened, burnt-out and, as one woman put it, “bloody knackered”.

We, as women, are seeking a greater individualism (as evidenced in the increasing focus on the Self and the use of phrases like self-care and self-love in ways that no longer reflect their original meaning) I feel, because we no longer share a ‘common form of life’ but remain subject to the norms which once upheld and maintained that common life.

How to reconcile that? How do we, as women, not isolate ourselves further by, understandably, seeking to distance ourselves from a broken communal system that has burdened and worn us out, yet build the communities that would nourish us? And how, especially, do we do this when that past of ‘communal jam-making’ we so often glorify is long gone and, as things now stand, we no longer share a ‘common form of life’.

Conway, D. (1996). Capitalism and Community. Social Philosophy and Policy, 13(1), 137–163. doi:10.1017/S0265052500001552

Schaumberg, R. L., & Skowronek, S. E. (2022). Shame Broadcasts Social Norms: The Positive Social Effects of Shame on Norm Acquisition and Normative Behavior. Psychological science, 33(8), 1257–1277. https://doi.org/10.1177/09567976221075303

Beale, J. (1986). Women in Ireland: Voices of Change. Gill & Macmillan.

Thanks Ali. And yes, very much resonate with what you describe. It's the challenge of creating / finding a Tribe that has room for the Individual

Thank you for putting words to this dilemma. I have such a longing for communal connection.